Gainsborough Old Hall Introduction. Gainsborough Old Hall is a late 15th century half-timbered manor house that stands close to the centre of the market town of Gainsborough in Lincolnshire; it has the river Trent to the west and the Parish church of All Saints’ to the east. Sir Thomas Burgh built the hall between 1475 and 1483 on the site of an earlier hall, and, apart from some later alterations, the fabric of the building is still substantially 15th century.

The hall was built in four stages, first, the great hall, which occupied the site of an earlier medieval hall-house. The brick built kitchen was constructed at the same time and was detached from the hall by some distance in order to minimise the risk of fire. Second to be built was the east range, this provided accommodation for the family. Both the ground and first floors have large salons, bounded on either side by two smaller rooms. Each of these rooms have fireplaces, however, later alterations make it impossible to appreciate their original appearance. The West range consisted of twelve self-contained apartments, four rooms on three floors. These were for guests and senior staff; each room has a fireplace and gare de robe. 1 There was no access from the west range to the rest of the house, and access to the upper rooms in the west range was via a spiral staircase on the outside of the building. Finally, in 1483 when Sir Thomas was ennobled and became first lord Burgh of Gainsborough, he had the tower built; this was purely to advertise his increased status. The tower has one polygonal room on each of its three floors, each of which has a gare de robe and fireplace. The tower also has a c.17th ghost last seen in the 1950s! Outside, extensive lands spread north and east; to the west, the hall is bounded by the river, and to the south was a formal physic garden together with a substantial mart yard. This hosted two fairs a year; it was the towns’ medieval market, and continued as a meeting place up to the 19th century when the southern part was used for building. The physic garden has recently been re-created. The Great Hall.

To the east of the great hall are two rooms, one above the other. The function of the downstairs room is unknown, but the upper room was the solar, the original bedroom of Sir Thomas and Lady Ann Burgh. This was also used as the "withdrawing" room for the ladies of the household, where they could sit by the fire and occupy themselves with needlecraft and other pursuits. A spy-hole enabled the ladies to see what was happening in the great hall beneath them. One common practice of the period was that of keeping small quantities of food, chicken legs, pies etc. in a cupboard, thus preventing night hunger. To the west of the great hall was the screen and minstrels’ gallery, now no longer in existence. Beyond the screen are three entrances; the one to the left leads to the pantry where food was stored, and the one to the right leads to the buttery, French for barrel store. This housed barrels of ale, mead and wine for immediate usage. The central passage leads to the kitchen. This was originally detached, but a brick-connecting corridor was added the late 16th or early 17th century; this has accommodation space above for the housekeepers and women servants’ sleeping quarters. Kitchen.

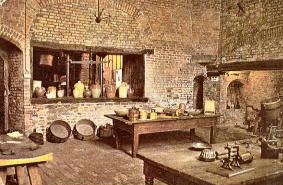

The chef was in charge of the day-to-day running of the kitchen and its numerous staff, who were all male; these people lived and slept in the kitchen. The clerk was responsible for keeping the accounts and for the ordering of items that the estate could not produce. He had his own office, in which was a locked cupboard for the storage of expensive spices and valuable salt and sugar Two further rooms abut the kitchen, the bakery, where bread was made, and the room for hanging game. The estate was almost self-sufficient; it produced it’s own game, farmed meat and poultry, fish, dairy produce, honey, vegetables, herbs and fruit, and flour and lard for bread and pastry. Life with the Burghs.

Court connections led to two royal visits, Richard III in October 1482 and Henry VIII in1541. On both occasions, the entire court, over 200 people, would have descended on the old hall. The recipe for the dinner that was prepared for Richard III is enclosed. 2 Henry VIIIs visit is less well documented; however, one of his courtiers, Philip Tyrwhitt, nephew to Lady Agnes Burgh, carved "Trust truth only" on the wall of a small room in the east range. The Tyrwhitts still live locally. The first husband of Catherine Parr, sixth wife of Henry VIII, was Edward, eldest son of the second Lord Burgh; however, she would have lived in the hall many years before Henry’s visit. The rumour that they met in the Old Hall is untrue.

The great hall was the centre of the running of the estate. Lord Burgh, or his steward in his absence, presided over the daily court. This dealt with all matters regarding the estate from disputes between tenants to poaching. The estate court was like a royal court in miniature. The leisure activities of the gentlemen of the household and their guests included hunting and hawking. Ladies’ pursuits were more sedentary, walking, needlecraft and reading. The Hickmans. In 1596 Thomas, fifth Lord Burgh died bankrupt and with no male heir; the old hall was sold to a London merchant called William Hickman. William immediately set about cladding the walls of the east range in brick; he also replaced the fireplaces and replaced the original windows with large, elegant bay windows. He created a third floor in the small south rooms of the east range by lowering the ceiling on both floors, thus making an extra room. Part of the floor on the first floor has been cut away to show this alteration. The ground floor room of these three was panelled at this time, and is believed to have become the family dining room. The bedroom above this is furnished in a similar manner to that listed in the probate inventory of 1625, made at the time of William’s death; these include "green taffeta curtains…and two pieces of tapestry work…" among others. The downstairs room at the north end of the east range was, according to the inventory, known as the garden room. It was decorated with "Secco fresco", an inexpensive wall painting to replace expensive hangings. Little survives, but it is still possible to make out the flowers, birds and butterflies that gave the room its name. The Hickmans were separatist sympathisers, and the nearby Scrooby congregation, who were to form part of the original "Mayflower" pilgrims, were supported by William and given permission to worship regularly in the great hall. Willoughby Hickman, a descendant of William, was knighted in 1643; he is believed to have played a major role in the battle of Gainsborough during the Civil War. Shortly after this, Matilda Hickman inherited the old hall. She did not marry, and willed the hall to her nephew on the understanding that he changed his name from Bacon to Hickman-Bacon. This name existed until the mid 20th century, when it reverted to Bacon. Sale In 1720, the Hickman-Bacon family had a smart Georgian manor house built at Thonock, two miles outside Gainsborough, and the "old" hall, as it became, fell into decline through neglect. It was used for numerous purposed after this; John Wesley preached in the great hall on several occasions. The house was also used as a bank, laundry and corn exchange at various times. The west range was converted into tenements, including a public house called the "Queen Adelaide." Between 1797 and 1856, the great hall was used as a theatre, and, during the 19th century, the first floor salon became the towns’ assembly rooms. It was during this period that the ceiling was raised eighteen inches; this explains the elegant carved beams and cornice and the crenulations along the top of the east range; both were added at this time, as were the fireplaces in the upper and lower salons. Sir Henry Hickman-Bacon decided to re-claim the old hall in the 1850s, and, with the aid of a young engineer called Denzil Ibbotson, made substantial structural alterations including new windows and elaborately carved coats of arms. After Henry’s death in the1870s the hall continued to decline until, by the mid 1940s, the west range was unsafe. Friends of Gainsborough Old Hall In 1949, Sir Edmond Bacon offered the hall to the town, and it was in imminent danger of being pulled down. A group of interested townspeople determined to prevent this; they formed themselves into the "Friends of the Old Hall," and rented the building for 1 shilling per annum from Sir Edmond. The hall was opened to the public and money was raised in order to carry out substantial repairs. Sir Edmond sold the old hall to the nation in 1970 for £1, and now English Heritage is responsible for the fabric of the building, and Lincolnshire County Council Museums Dept., with the aid of the Friends, the day-to-day running of the building. The final part of the hall to be restored was the derelict west range, this was completed in 1988. Because the structure was in such poor condition, it was impossible to restore it to its 15th century state. Instead, the ground floor now houses the entrance and shop, and the upstairs a small gallery. Of the rest of the building, the great hall and kitchen are extant, while in the east range, the garden room houses a small restaurant and the ground floor salon is used for public functions. The house is open as a living museum and community centre and re-enactments of Burgh family life, traditional craft fairs and other functions are held often. Sir Nicholas Bacon, Sir Edmond’s nephew, is president of the Friends and actively involved with the Old Hall.

Notes 1 Gare de RobeIt was found that ammonia fumes killed off any fleas or lice in clothes and also protected then from moths. For this reason clothes were hung in the toilet area and it was known as a 'gare de robe'. Over the years gare de robe became shortened to wardrobe and, thankfully, the habit of storing clothes in toilets also died out.

2 Menu for King Richard 111Minstrels played throughout the banquet and a trumpet fanfare announced the arrival of each new dish. These are many and varied and included:- Pottage of stewed broth Baked pies of calves feet Whole side of roast beef Boiled rabbits with puddings Baked cranes and bustards White puddings of hogs liver Baked sparrow and other smaller birds Pestells of red deer Cream of almonds Marchpaynes

3 Rules of EtiquetteDo not touch the salt in the salter cellar with any meat,' but lay salt honestly on your trencher for that is the courtesy" People ate with their fingers. Forks had not been invented and each person carried their own knife for cutting meat. Using the fingers made hand washing very important. "Before meals it is right to wash your hands openly, even though you have no need to do so, in order that those who dip their fingers in the same dish as yourself may know for certain that you have cleaned them. " Each table was provided with a bowl of water, scented with flower petals in order for diners to keep their hands clean. It was also considered very poor manners to try and get the best food. "He who pokes about on the platter, searching presumably for the best bits of food, is unpleasant and annoys his neighbour at dinner. "So the table etiquette in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, although different, was as strict as that of any house, hotel or restaurant today.

|

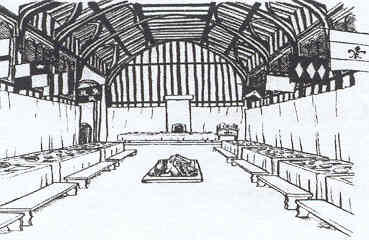

The great hall was constructed around six elaborate roof trusses and supporting piers that were carved from green oak; these formed the mainframe and structure of the building around which everything else fitted. The process of medieval building was similar to putting together a huge three-dimensional jigsaw, each joint was individually marked and these marks corresponded so that each joint fitted its neighbour exactly. The joints were tenon and mortice, fixed with dowelling pegs. Unusually for such a large space, there are no cross-braces, thus enabling the full grandeur of the building to be appreciated. The hall was heated by a central hearth, and smoke would have escaped through the lantern in the roof. This was removed some years ago for safety reasons. Twelve leaded windows, six on either side, occupied the upper register of the twelve bays, thus allowing constant daylight to flood in. In the late 16th century the entire easternmost bay on the north wall was replaced by a massive stone bay window, possibly from a redundant monastery; this gave extra light to the east end of the hall. At the same time, an impressive newel staircase was added, replacing a spiral staircase. The new staircase opens onto a "perambulating area" overlooking the garden; this was used by ladies of the household when it was too wet to walk outside.

The great hall was constructed around six elaborate roof trusses and supporting piers that were carved from green oak; these formed the mainframe and structure of the building around which everything else fitted. The process of medieval building was similar to putting together a huge three-dimensional jigsaw, each joint was individually marked and these marks corresponded so that each joint fitted its neighbour exactly. The joints were tenon and mortice, fixed with dowelling pegs. Unusually for such a large space, there are no cross-braces, thus enabling the full grandeur of the building to be appreciated. The hall was heated by a central hearth, and smoke would have escaped through the lantern in the roof. This was removed some years ago for safety reasons. Twelve leaded windows, six on either side, occupied the upper register of the twelve bays, thus allowing constant daylight to flood in. In the late 16th century the entire easternmost bay on the north wall was replaced by a massive stone bay window, possibly from a redundant monastery; this gave extra light to the east end of the hall. At the same time, an impressive newel staircase was added, replacing a spiral staircase. The new staircase opens onto a "perambulating area" overlooking the garden; this was used by ladies of the household when it was too wet to walk outside. The brick-built kitchen is one of the finest examples of its type in the country. It has two massive fireplaces, one for spit roasting and the other for cooking potages, (there would have been a pot of soup constantly cooking, into which vegetables would have been added daily.) The kitchen also has a "pilot light," a small fire that was kept constantly burning, and two bread ovens. Structurally, it is similar to the great hall, but much less elaborate. Roughly hewn roof trusses hold up the exposed pan tile roof, it also has a lantern to get rid of the smoke. The present lantern is a c. 19th replacement.

The brick-built kitchen is one of the finest examples of its type in the country. It has two massive fireplaces, one for spit roasting and the other for cooking potages, (there would have been a pot of soup constantly cooking, into which vegetables would have been added daily.) The kitchen also has a "pilot light," a small fire that was kept constantly burning, and two bread ovens. Structurally, it is similar to the great hall, but much less elaborate. Roughly hewn roof trusses hold up the exposed pan tile roof, it also has a lantern to get rid of the smoke. The present lantern is a c. 19th replacement. Altogether, there were five Lord Burghs connected with the Old Hall. Thomas, the first lord, served as senior courtier to Edward V, Richard III and Henry VII. Thomas, the third lord Burgh was influential in the court of Henry VIII, and Thomas, fifth lord Burgh was a high-ranking soldier who served Elizabeth 1st. Had he not died young, he would almost certainly have been granted an Earldom.

Altogether, there were five Lord Burghs connected with the Old Hall. Thomas, the first lord, served as senior courtier to Edward V, Richard III and Henry VII. Thomas, the third lord Burgh was influential in the court of Henry VIII, and Thomas, fifth lord Burgh was a high-ranking soldier who served Elizabeth 1st. Had he not died young, he would almost certainly have been granted an Earldom. Mealtimes in the Burgh household were formal; Lord Burgh sat on a canopied chair, surrounded by his family and important guests, at high table in the east end of the great hall. Less important guests and servants would sit on benches at long tables, in order of rank, on either side of the hall. Etiquette was very important; the public washing of hands was a necessity, as was the circumspect use of salt, a valuable commodity. Small portions of salt were put into a dedicated space on each person’s wooden eating platter. Only those at top table had the privilege of using pewter, silver or gold plate, and again its use depended on rank. 3

Mealtimes in the Burgh household were formal; Lord Burgh sat on a canopied chair, surrounded by his family and important guests, at high table in the east end of the great hall. Less important guests and servants would sit on benches at long tables, in order of rank, on either side of the hall. Etiquette was very important; the public washing of hands was a necessity, as was the circumspect use of salt, a valuable commodity. Small portions of salt were put into a dedicated space on each person’s wooden eating platter. Only those at top table had the privilege of using pewter, silver or gold plate, and again its use depended on rank. 3